Definition of a Concept Map

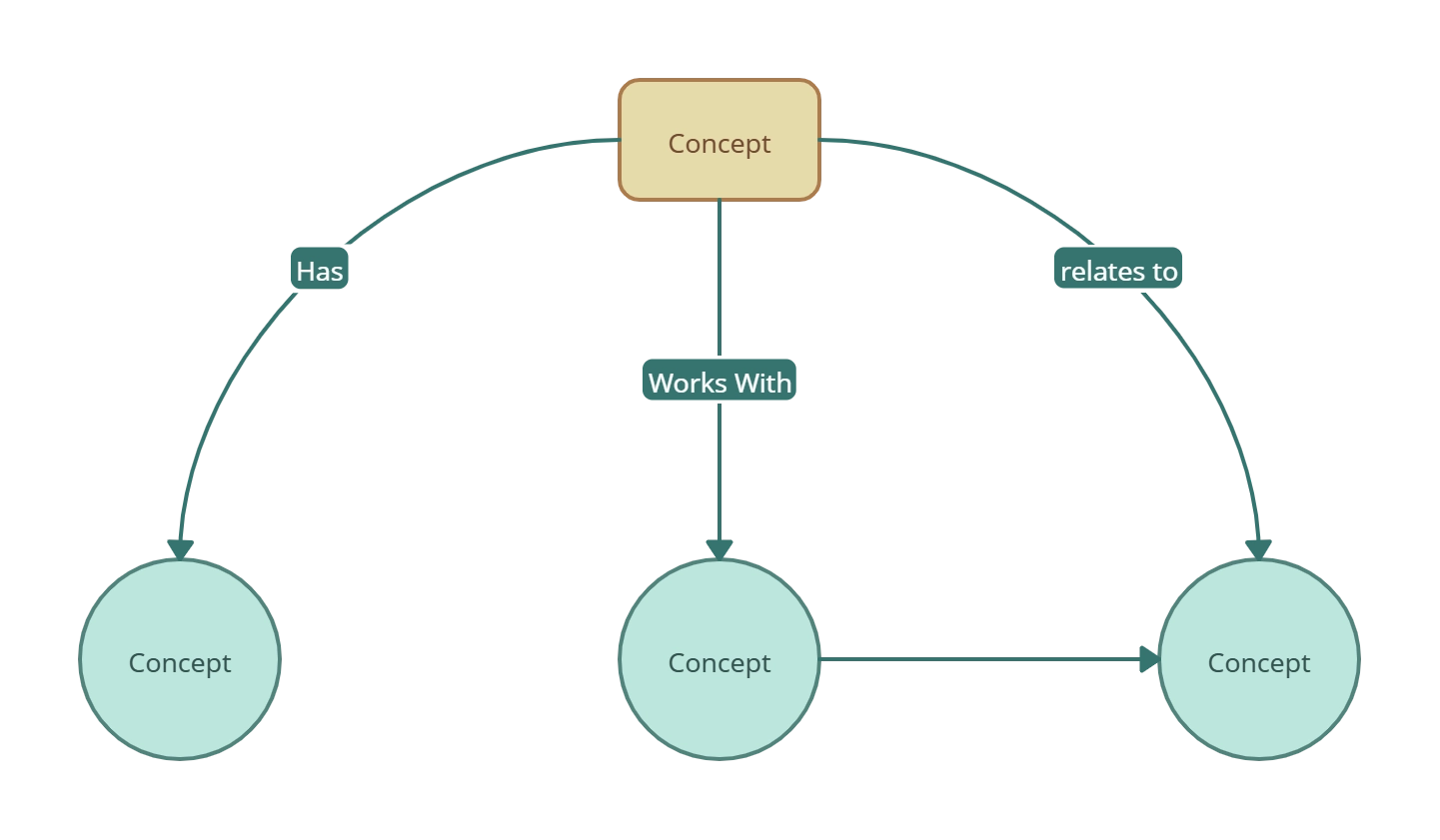

Concept map is a visual tool used to represent relationships between different concepts. They help organize and structure knowledge in a way that makes connections and hierarchies clear. They contain,

Concepts/ideas - Usually shown using circles, ovals or rectangles with the concept added as a text inside.

Relationships - Also knowns as arcs, they are shown as arrows with the arrow name describing the relationship.

Types of Concept Maps

Concept maps come in various forms, each serving a unique purpose depending on the information being visualized. Understanding these types can help you choose the most effective structure for your needs. The most common types of concept maps include:

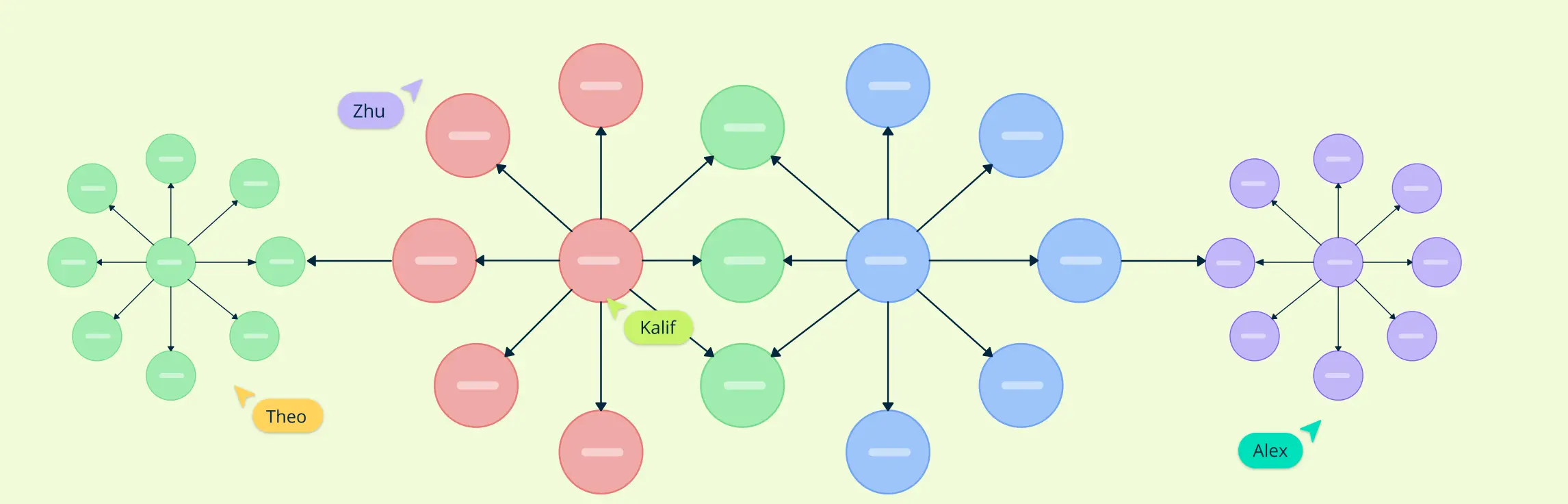

- Spider Maps: Ideal for brainstorming, spider maps place the central concept at the center, with related ideas radiating outward like a web.

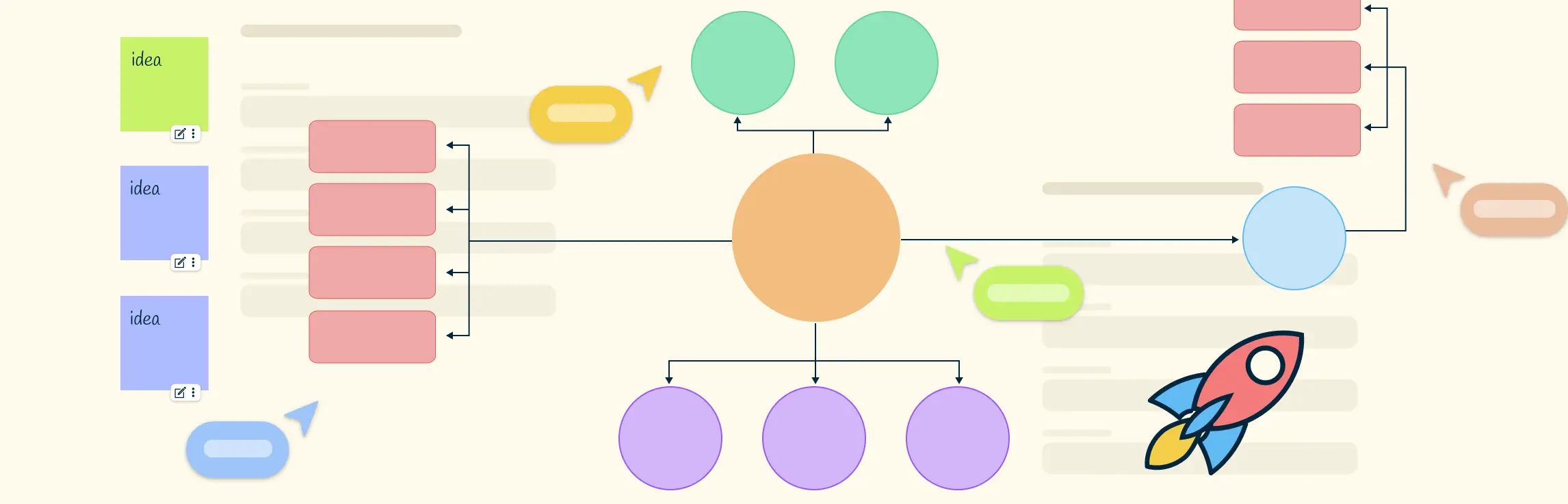

- Flowcharts: Used to illustrate processes or workflows, flowcharts show sequential relationships and step-by-step progressions.

- Hierarchy Maps: These maps organize information in a top-down structure, starting with the main concept and branching into sub-concepts, making them perfect for showcasing levels of importance or dependency.

- System Maps: Designed to represent complex systems, these maps highlight interconnections between multiple elements, showing how different components influence one another.

How to Create an Effective Concept Map

Identify the Central Concept: Start by selecting the main idea or topic you want to explore.

Identify Key Related Concepts: List all major ideas or subtopics related to the central concept.

Organize Concepts Hierarchically: Arrange the related concepts around the central concept in a hierarchical structure—from general to specific.

Draw Connections Between Concepts: Connect the central concept to related ideas using lines or arrows ensuring that each connection represents a meaningful relationship.

Add Linking Phrases for Clarity: On each connecting line, include linking words or phrases (e.g., “results in,” “is part of,” or “contributes to”) that explain the relationship between concepts.

Incorporate Cross-Links: Create cross-links between concepts from different branches of the map.

Review and Refine the Concept Map: Evaluate the concept map for clarity, accuracy, and completeness. Adjust the structure, add missing links, or remove irrelevant concepts as needed.

This is a simple breakdown of the steps of making a concept map. Here’s a more detailed explanation of how to create a concept maps.

Concept Map Templates for Various Use Cases

Concept mapping is a powerful method with broad benefits and diverse applications across many industries. These visual tools help in organizing information, improving comprehension, and facilitating decision-making processes. Let’s delve into how concept maps are applied in different fields.

1. Concept Map Templates for Business and Strategic Planning

2. Concept Map Templates for Education and Learning Enhancement

3. Concept Map Templates for Healthcare and Patient Care Management

4. Concept Map Templates for Research and Knowledge Management

5. Concept Map Templates for Marketing Strategy and Campaign Planning

6. Concept Map Templates for Problem-Solving and Decision-Making

FAQs About Concept Maps

What is the main purpose of a concept map?

How is a concept map different from a mind map?

When should I use a concept map?

Concept maps are best used when you need to understand, organize, or present complex information. They’re ideal for:

- Studying and learning: To break down and visualize complex subjects.

- Strategic planning: For mapping business strategies and project workflows.

- Problem-solving: To identify relationships and dependencies between key factors.

- Research and analysis: To organize literature reviews and hypothesis development.

- Team collaboration: To improve communication by providing a shared understanding of ideas and processes.

What are the key components of a concept map?

A concept map typically includes:

- Central concept: The main idea or theme the map focuses on.

- Nodes: Secondary ideas or concepts connected to the central theme.

- Linking lines/arrows: Visual connectors showing relationships between concepts.

- Linking phrases: Descriptive words or short phrases on the connecting lines that explain how the concepts relate (e.g., “leads to,” “depends on,” “is part of”).

- Cross-links: Connections between different parts of the map, illustrating how various ideas interrelate.

What are the Advantages of Concept Mapping?

- Enhances Understanding of Complex Topics

- Improves Memory Retention and Recall

- Promotes Critical Thinking and Deeper Analysis

- Simplifies Presentation of Complex Information

- Facilitates Collaboration and Communication

- Supports Effective Planning and Problem-Solving

- Encourages Creativity and Innovation

What are the Disadvantages of Concept Mapping?

- Time-Consuming to Create for Complex Topics

- Requires Familiarity with Concept Mapping Techniques

- Can Become Overly Complicated and Cluttered

- Not Always Suitable for Linear Processes

- Subjectivity in Structure and Organization

- Limited Detail in Complex Relationships

Resources:

Davies, M. (2010). Concept mapping, Mind Mapping and Argument mapping: What Are the Differences and Do They Matter? Higher Education, [online] 62(3), pp.279–301. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-010-9387-6.

Gao, H., Shen, E., Losh, S. and Turner, J. (2007). A Review of Studies on Collaborative Concept Mapping: What Have We Learned About the Technique and What Is Next? Journal of Interactive Learning Research, [online] 18(4), pp.479–492. Available at: https://www.learntechlib.org/noaccess/21702/.

Watson, G.R. (1989). What is… Concept Mapping? Medical Teacher, 11(3-4), pp.265–269. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/01421598909146411.